Whenever the topic of asset reuse rears its head once more in the pantheon of video game debate, its point of origin can usually be traced back to the impending arrival of a hotly anticipated sequel. Provoking the discussion in the first place is often a single disingenuous barb, gleefully concocted from equal parts ignorance and arrogance, and parroted with an enviable level of confidence. Propelled by tribalism and detached from the science of game design, the loudest opinions are often the ones that gain the most traction. Reusing a set of choreographed character animations across successive games is tantamount to a crime, after all. Modern game discourse is predictable. It is self-perpetuating and cyclical—what’s being talked about in the present will be exactly what we’re talking about once again in the future. Difficulty, resolution, sequels, exclusivity and accessibility are all inherent to the modern experience. They’re all topics that deserve to be scrutinised and questioned—especially as the medium passes certain technological milestones. Though the reality of any such discussions tends to leave a lot to be desired.

Since first becoming enamoured with the Yakuza series through prequel instalment Yakuza 0 back in 2017, i’ve steadily made my way through all of the mainline entries in chronological order, while also taking a detour along the way to explore spinoff series Judgment. Throughout that time, I have walked back and forth beneath the Tenkaichi Street gate in the borough of Kamurocho more times than I can count. I have fought anarchic villains across the very same rooftops and beaten down droves of grunts along the very same streets. And I have gradually grown into the iconic stone grey suit and slacks of the city’s most revered defender, an image that is as synonymous with fist-driven ferocity as it is with proper cabaret club etiquette. Kamurocho makes an appearance in every modern game within the Yakuza and Judgment series’. Although such regular returns have given it plenty of opportunities to overstay its welcome, the glow of the night-time neon has yet to dim and navigating its labyrinthian sprawl is never uninteresting. Kamurocho just has a knack for enduring, and having explored the city across four different virtual decades, it’s clear that a lot of its charm comes from it being a lynchpin within an ever-evolving story. One way or another, all paths filter back to that small patch of land, an island of concrete in an ocean of glass.

The book never truly closes on Kamurocho, its rich and infamous history being iterated and reiterated upon with every new instalment in the series. And over time, Kamurocho and the Yakuza series have coexisted long enough so as to become completely inextricable from one another. Many expansive modern sequels often tend to favour newer pastures, preferring to progress their story against an entirely new backdrop rather than dig in roots someplace familiar. In this sense, the Yakuza series is no different. Alongside Kamurocho, sequels and prequels alike have introduced the player to almost a dozen different environments in total, ranging from the sunny shores of Ryukyu to the mountainside hovel of Onomichi, the first playable location in the series not to be dubbed with its own fictionalised name. In Like a Dragon meanwhile, the new map Isezaki Ijincho proved to be the series’ largest environment to date, housing everything from authentic eateries and gambling halls to the lesser known pleasures of kart racing and can collecting. Kamurocho meanwhile always remains on the periphery, just out of sight. Though the story may predominantly unfold someplace else, Tokyo’s premiere destination for everything from nostalgic SEGA classics to impromptu street fights is only ever a taxi ride away.

* * *

Even if telling the next volume of a story doesn’t depend on the inclusion of a completely new setting, then just changing things up for the sake of variety isn’t necessarily the worst idea. In the case of parkour-centric zombie thriller Dying Light, developers Techland pushed the sequel away from the concrete playground of Harran, choosing to evolve their story within the disparate survivor enclave of Villedor. And in the Fallout series, every successive game migrates the setting to newer pastures, with over half a dozen different titles encapsulating a virtual timeline that spans centuries of apocalyptic conflict. Delving into the lore of such games tends to bring back a lot of familiar memories—typically, sequels will reference events that the player has been at the very heart of, or even influenced directly. But these tales are often told in whispers and hearsay, the triumphs of the past either lost to time or disputed enough within the canon that they remain open to interpretation. By establishing Kamurocho as the series’ centrepiece from the very beginning, the narratives of the Yakuza series, and thus the actions of the player, become permanently intertwined with its history. Rather than calling back to previous events that are beyond your influence, your adventures in Kamurocho are canonised in infamy. And because of this, every single snaking alleyway and bustling storefront gradually becomes a different exhibit within a comprehensive museum of violence. By the time that I returned to Kamurocho once more as Kazuma Kiryu in Yakuza 6, which back then seemed like it would be the Dragon of Dojima’s final outing, there wasn’t a single place left in the city where I hadn’t raised my fists. Every landmark smoulders with the consequences of choices made over a breadth of different games. And the importance of establishing such an extensive lore makes it easy to look forward to repeated visits, if only to see how the city is faring after its most recent brush with total annihilation.

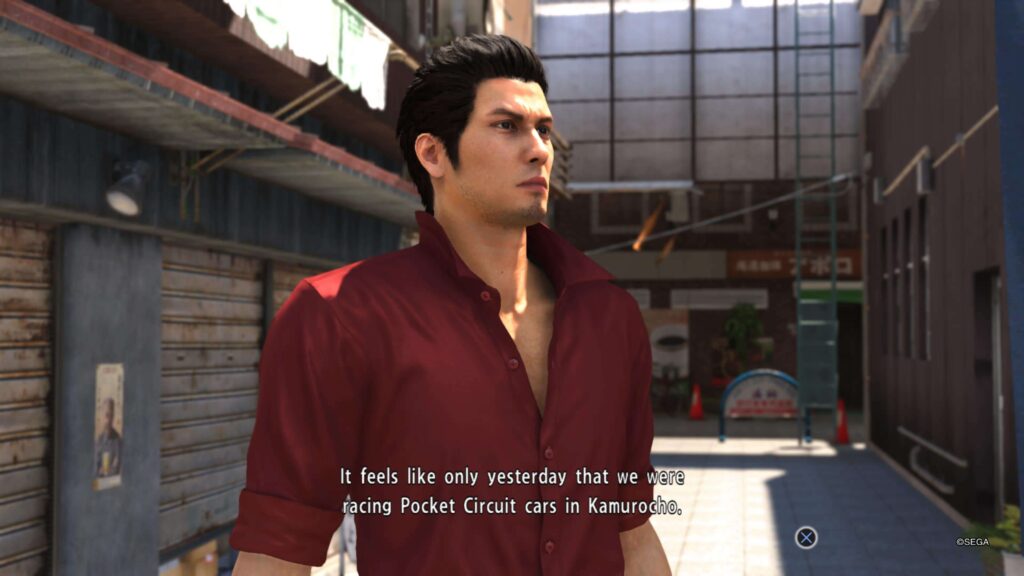

This emphasis on ensuring that both people and places alike are intertwined with their collective histories only supports the ease with which developers Ryu Ga Gotuku are able to dredge something up from Kamurocho’s past and make it relevant again in its present. A side-quest here, a line of dialogue there—even beyond the main narrative, where the battles of the past are often used to fuel wars in the future, there’s a lot of stock placed in the ripple effect. Calling back to prior events, even momentarily, casts that very history in stone. And having played an active role in writing that history, things tend to take on a much greater weight of significance. In Yakuza Kiwami, Kiryu singlehandedly dismantles a street gang uprising through sheer brunt force, tearing through their ranks fist-first until the entire hierarchy has been completely eviscerated. In Kiwami 2, a chance encounter through a sub-story reunites Kiryu with two former members of the gang, now on the path to reform after having put that life behind them.

The Yakuza games are full of examples like this, where minor characters crop up in unremarkable fashion to remind you once more that there is a persistent world in motion behind the events of the main narrative. Without ever engaging in any sub-stories, Kiryu’s tale is one of non-stop breathless action and ceaseless confrontation. But to slow down for a moment and take in the sights and sounds of the city is to truly appreciate the depth that exists there. Outside of the repeated bomb detonations, bloody clan conflicts, turf wars, shootouts and riots, to much of its citizenry, Kamurocho is just another normal borough. In between those occasional cacophonies of violence, arcades will continue to ring, barkers will continue to yell, and gradually, the bustle builds back up as life returns to its usual pace largely unaware of the context behind the war of the night before.

So much has befallen Kamurocho throughout the decades that it’s often easy to miss some of the stories and sidebars that occur beyond the scope of the latest all-out clan warfare. When Kiryu, Ichiban, Yagami or any of the core protagonists are able to explore the district in their free time, they’re never left wanting for things to do. Game after game, developers Ryu Ga Gotoku refresh the attractions of Kamurocho from top to bottom in order to ensure that every recurring visit brings with it something completely new. Just as the Yakuza series has earned plaudits for its gripping crime drama and bombastic action, so has it for the completely converse way with which it handles moments of levity and lightheartedness. There is no character who better encompasses the capability for both magnificent violence and disarming tolerance than Kazuma Kiryu, and no better canvas for it all than Kamurocho. Firstly, you’ve got your SEGA arcade classics, fully playable titles from the publishers’ back-catalogue that can be found inside of any amusement hub. Games like Virtua Fighter, Fantasy Zone, Space Harrier, Super Hang-On and Puyo-Puyo can be found in multiple games across both the Yakuza and Judgment series’. Bolstering these recurring titles are the likes of OutRun, Fighting Vipers and Taiko no Tatsujin, with more niche cabinet titles like Motor Raid and Sonic the Fighters also making an appearance. If you’re after something more traditional, then Japanese cultural staples like Mahjong, Koi-Koi and Oichu-Kabu can be found inside gambling halls in multiple different games, usually alongside Western favourites like Roulette, Poker and Blackjack. And that’s not to mention the litany of other experiences you may discover along your travels, like fishing, golf, disco dancing, taxi driving, slot-car racing, karaoke, street fighting, skateboarding and even hostess training. There’s a seemingly endless list of uniquely enjoyable distractions that evolve in tandem with their environment. What’s popular inevitably changes with the times, and to that effect, the Yakuza games—largely evidenced through Kamurocho and its sister locale Sotenbori—provide a wonderful look into the cultural shift that occurs as years pass. Like peering into the reflection of a different age, many of the returning environments of Yakuza function as veritable time capsules of Japanese culture scaled down into a succinct digital form. Although they may have a heavy fictionalised slant to them, everything separated from gangland politics bears its own realistic shadow. From its eateries to arcades, known brands to knock-offs, anchored in the familiarity of well-worn streets and alleyways is the kind of place where every blemish has a story behind it. And much like the place you grew up in, treading back on that hallowed ground always makes you cast your mind back to the past.

* * *

With the release of Yakuza: Like a Dragon—or simply Like a Dragon as the series will be known as going forward—the mainline games pivoted from their classic action adventure beat-‘em-up style to being entirely turn-based affairs, with every enemy encounter now playing out one move at a time. Yet despite that massive, near unprecedented revision into something altogether different, Yakuza: Like a Dragon didn’t feel all that unfamiliar. Not just in the recognisable sights and sounds of neon-lit storefronts and bellowing barkers, Like a Dragon was a culmination of the series’ growth up to that point, repurposing entire environments in the cases of Kamurocho and Sotenbori, as well as iconic enemy move-sets, sound effects and character animations. The end result was a game that was a wholly new package draped in familiar trappings, and a wonderfully realised metamorphosis. Like a Dragon’s critical and commercial success was a testament to a development team assured in the knowledge of how to best utilise their extensive library of creations. To celebrate Ryu Ga Gotoku for producing games of immense quality in such relatively short amounts of time is to acknowledge that it simply wouldn’t be possible free from their iterative process. In the nine year period that began with the release of Yakuza 0 and its subsequent arrival into the Western mainstream, the series has seen two complete mainline remakes, a spin-off remake, a trio of remasters, 2 brand new mainline games, 2 in-universe spin-off games, a series first DLC expansion and, most recently, a smaller title meant to bridge the gap between Like a Dragon and its sequel, which is set to arrive in February of 2024. Such a staggering level of output might point to Ryu Ga Gotoku boasting thousands of employees across half a dozen subsidiary studios, with its games tied to the very same annualised conveyer belt as your typically uninspired sports titles. The reality however is simply much more straightforward.

The Yakuza series is a breath of fresh air in a medium where the open-world space is treated like a one-size-fits-all content delivery system, and where quantity is very often valued higher than quality. With such a large area to fill, scattered iconography dominates these lands as content is parcelled up and distributed evenly between their borders. The Yakuza games cannot compete when it comes to size, but their smaller, densely populated environments serve as their own critique of open-world formlessness. Kamurocho appears in every mainline game but is never an unwelcome sight. And the main reason as to why lies in the level of purpose that developers Ryu Ga Gotoku are able to make for it. Kamurocho doesn’t return because it necessarily has to, but because it’s so malleable and versatile. In some games, its only required role is that of a backdrop used primarily to nudge the story forward. In others, it’s a fully fledged hub of sights to see, things to do and people to interact with. But no matter where the story takes place, there’s never any question of the level of quality to be expected. The Yakuza games are rich with substance and flush with a seemingly endless amount of content. Even the mini games captivate so easily because there’s a depth to them that puts most other open-world fare to shame. Asset reuse may be rather commonplace across the industry at large, but RGG are perhaps the masters of its implementation. And in lieu of the budgetary excess boasted by many of its contemporaries, it takes a mastery of things like asset reuse, mini-game design and even in-game emulation to ensure that games like the Yakuza series are capable of occupying the same spotlight as many of the giants of the industry.

Maybe getting older has something to do with it. The Yakuza games were easy to get into because of just how much there was to immediately see and do. And they were easy to stick with because everything that transpires does so within its own little virtual archipelago of neighbouring villages, towns and cities. It’s a little daunting to first run my eyes over a game’s map and notice that it’s big enough to warrant its own cloud coverage. But it’s much less so returning to someplace immediately familiar to me, especially in order to make another imprint upon its history. The thrill of discovery and of lifting the veil of a virtual world isn’t something entirely inherent to uncharted lands. Kamurocho is a bastion of change. And what exactly has changed about it isn’t plainly evident in the contours of its streets and walkways. Like any other game environment, those featured in the Yakuza & Like a Dragon games beg to explored. It’s just a little more straightforward when your average environment isn’t any more expansive than your local bus route. As long as the gates of Kamurocho remain open to me, i’ll gladly keep stopping by for a visit. Even as the book of Kiryu nears its final, ultimate end, the dragon’s lair has built a mythos all its own. If Kamurocho has proven anything throughout the series, it’s that it is capable of outlasting even the strongest of warriors.