The spacefaring adventure of The Outer Worlds begins as they all do. From the moment that alien grass first crunches beneath your feet, the yearning for discovery sends you soaring across the stars, a single spark catalysing a venture into the unknown. In The Outer Worlds, the search for answers to unasked questions drives a journey that spans the breadth of one system in particular—a refuge for humanity that has been misshapen into a haven for Earth’s departed elite. Across Halcyon, a colony shared by a conglomerate of corporations that don’t so much employ workers as own them outright, all that’s needed to stoke the flames of exploration is a brief subjection to ad-slogans and catchy branded jingles. By the time that each melody worms its way into your head and buries itself in your consciousness, the heavy fog of capitalistic greed begins to numb you to the touch. Inevitably, no one sets foot in Halycon without succumbing the lights and sounds of company sanctioned indoctrination.

The corporate corruption detailed within The Outer Worlds is laid on thick from the off, with your very first conversation a quick-fire education in the brand reverence that pervades every class and creed. Corporations are treated as religions in the colony, and as for the few sanctioned faiths that have survived the theologic bleaching, independent thinking is bound by an adherence to product worship. The world that Obsidian has built revolves around this idea of unchecked capitalism, where rampant profiteering and brand subservience is tantamount to law. It’s a darkly satire that riffs on everything from societal inequality to bureaucratic blockading, while remaining unerringly persistent even as it regularly fluctuates in tone. Recounted in equal measure are stories of workers perishing on production lines, propaganda-driven tales of interplanetary war, and the cartoonish evil of government higher-ups struggling to maintain the status quo. But all of it is the reality in a colony wrought by a damning societal division, and where such a stellar commitment to world-building illuminates even the darkest recesses of this delightfully wretched culture.

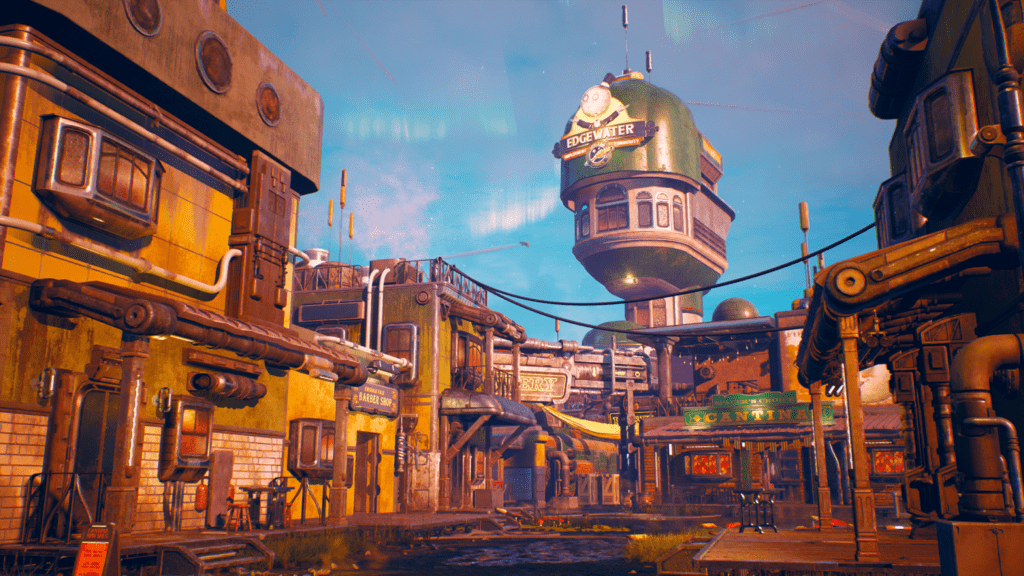

Influenced largely by the burgeoning design movement of the gilded age and rich in art nouveau substance, the visual direction of The Outer Worlds is rife with the essence of discovery. Similar to how its anti-capitalist and anti-collectivist themes make up such a prominent part of the game’s character, its aesthetic design follows suit with its own distinctly overindulgent style. Every settlement, marketplace and township is steeped in the trappings of an artistic revolution, with the wondrous depiction of its cosmic renaissance a foundation upon which its themes are able to thrive. And such an appreciation for its own visual decadence is all the more important when it comes to aptly characterising the colony’s many ills. An emphasis on making lore easily accessible through an adept usage of visual storytelling allows for what is a relatively small game to seem that much larger. You will visit around a dozen or so unique locations throughout your journey, some for hours, others for minutes, but no matter how long you spend with each, you’re able to garner a tremendous understanding of both larger societal problems and many of the smaller conflicts that are tucked beneath the surface. In its faultless consistency, The Outer Worlds is able to first capture your attention, and then continually invigorate your investment in its world with consummate ease. Evident in its ornate architecture, product packaging and clothing design, every fibre of the game has been polished with the same unwavering attention to detail. And even in the wilds, creature design and blossoming flora ruminates with a tinge of classic sci-fi pulp, though its colour palettes often lean a little too close to being uncomfortably oversaturated.

THE OMNISCIENCE OF THE BOARD MAKES FOR A TERRIFYING REALITY—HALCYON IS THEIRS, AND NO HELP IS COMING

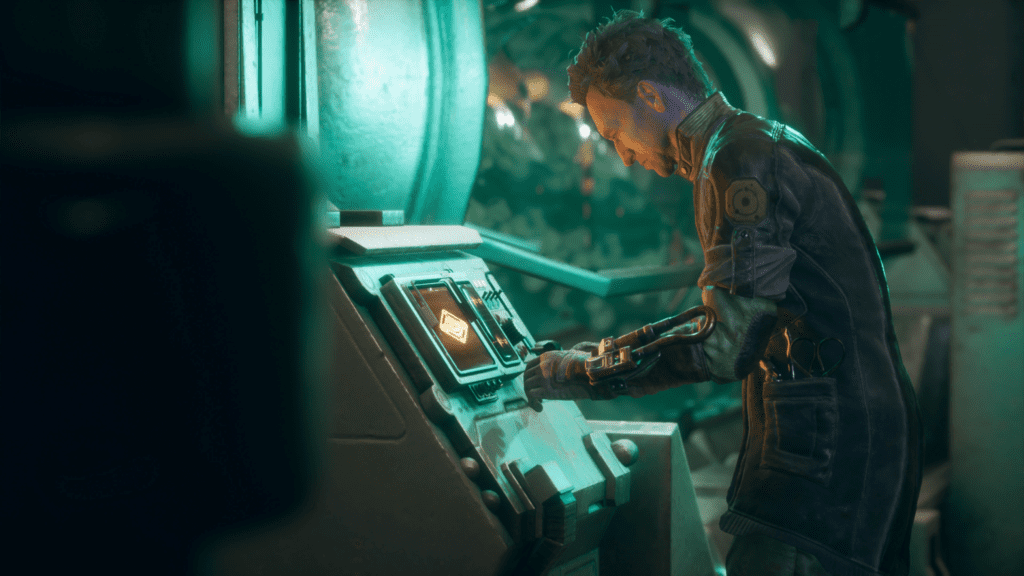

With no voiced protagonist, The Outer Worlds is able to grow its roots and prosper as a more traditional, choice-based RPG. The options offered during character creation are plentiful, providing you with a generously sized space in which to construct a persona all your own. The core elements of your character are integral to the way in which you perceive many aspects of the story, so no matter how you choose to approach life in the colony, your strengths and flaws will always play an important role. Provoking a unique response from someone due to your aptitude within a particular skillset is an intuitive, enjoyable way of controlling a conversation. And though you may ultimately reach the same conclusion, the agency it offers makes for an excellent sense of ownership over your character’s actions. The building blocks that comprise your identity are diverse enough to avoid being resigned to only a few set archetypes, but when combined with many of the other perks and abilities that you will unlock as you progress, your sense of individuality becomes somewhat diluted. Elevating attributes beneath the core skill headings unlocks incremental bonuses, but none of them really seem to elevate combat in such a way that the new Tactical Time Dilation ability becomes any less integral to its outcome. Progressing through the medical tree for example allows you to treat your medical inhaler like a mortar and pestle, combining additional ingredients together for more potent healing. While an initially interesting upgrade, even when playing on hard difficulty there was rarely an encounter taxing enough to warrant such an investment in my own self-preservation. Similarly, levelling of the engineering tree will eventually yield the chance to obtain modifications when breaking down gear, but these are so commonly found in the world anyway that you simply won’t be able to make use of them all. And when it comes to perks, rarely do bonuses in carry capacity and the recharge rate of companion abilities do anything other than further trivialise existing systems. Though the structure of The Outer Worlds is remarkably lean given its ambitious scope, its excesses hang in the air like bad habits, seemingly the result of being unable to scale down mechanics that would’ve likely had a stronger impact within an open-world setting. It’s a problem that’s difficult to overcome, and due to its influence over many of the game’s systems, one that adversely affects the inherent challenge of survival that the story proposes.

There is an undeniable strength to the game’s diplomatic aspects, but too often I found myself tuning out as soon as the lead and plasma started flying. Through use of Tactical Time Dilation, you are able to slow the pace of battle in order to analyse and target enemy weak points, allowing you to place your shots with an executioner’s precision. And with a single press of a button, you can also order your companions to strike a target with a humorously executed finishing move, something that had me rotating my accompanying allies regularly in order to find the best possible combination of their abilities. Both of these certainly add a little extra panache to firefights, but the biggest problem is that shooting a rifle or swinging a club feels terribly dull and outright unsatisfying. Outside of the game’s five rarified science gadgets, weapons are plainly lacking in responsive feedback, each of them devoid of the receptiveness that makes actions such as reloading feel light and unencumbered. And aside from the infectious waves of the n-ray element, there’s little else out there that really sparks the imagination. Even looting becomes laborious after a time, the corpses of your defeated all offering the same array of currency, ammo and food items. A large symptom of the problem is that you’re given too much, too often, which very quickly leads to things like quest rewards and vendor discounts seeming entirely inconsequential. Passively inundated with everything you’ll ever need, it isn’t long before the distinct lack of variety in gear and equipment becomes plainly noticeable. By the time that your pockets are overflowing with bit cartridges, ammunition and high-end rifles, there’s nothing left for the game to offer that could possibly tempt you. At that point, frequent encounters do little more than blockade your progress, and will have you longing for the next ceasefire.

Attempts at condensing such a large scale experience into something much more succinct have a telling impact upon the narrative, too. Driven by a wonderful cast of characters and brought to life through its excellent writing, the story of The Outer Worlds is short and to the point. But as is the case with several of its companion quests and other globetrotting distractions, there’s a certain abruptness to the way in which many of its plot threads come to a close. This is perhaps no more evident than at the game’s conclusion, which not only follows the unveiling of a grand mystery with a jarring cut to black, but also prevents you from continuing beyond the end credits. The Outer Worlds struggles when it comes to defining its form as an RPG, but it excels wholeheartedly in its creation of beautiful worlds and its depiction of the contemptible culture killing them. As the launching platform for a sci-fi saga, The Outer Worlds is infectiously charming and delightfully insidious in equal measure, beckoning you to see it all with an irrepressible enthusiasm. But even as a standalone experience, Obsidian’s latest endeavour was a much needed palette cleanser, and one that excels on the merit of its dedication to player choice.