Image Credits: Vinny GRed + Andre K + Quiet

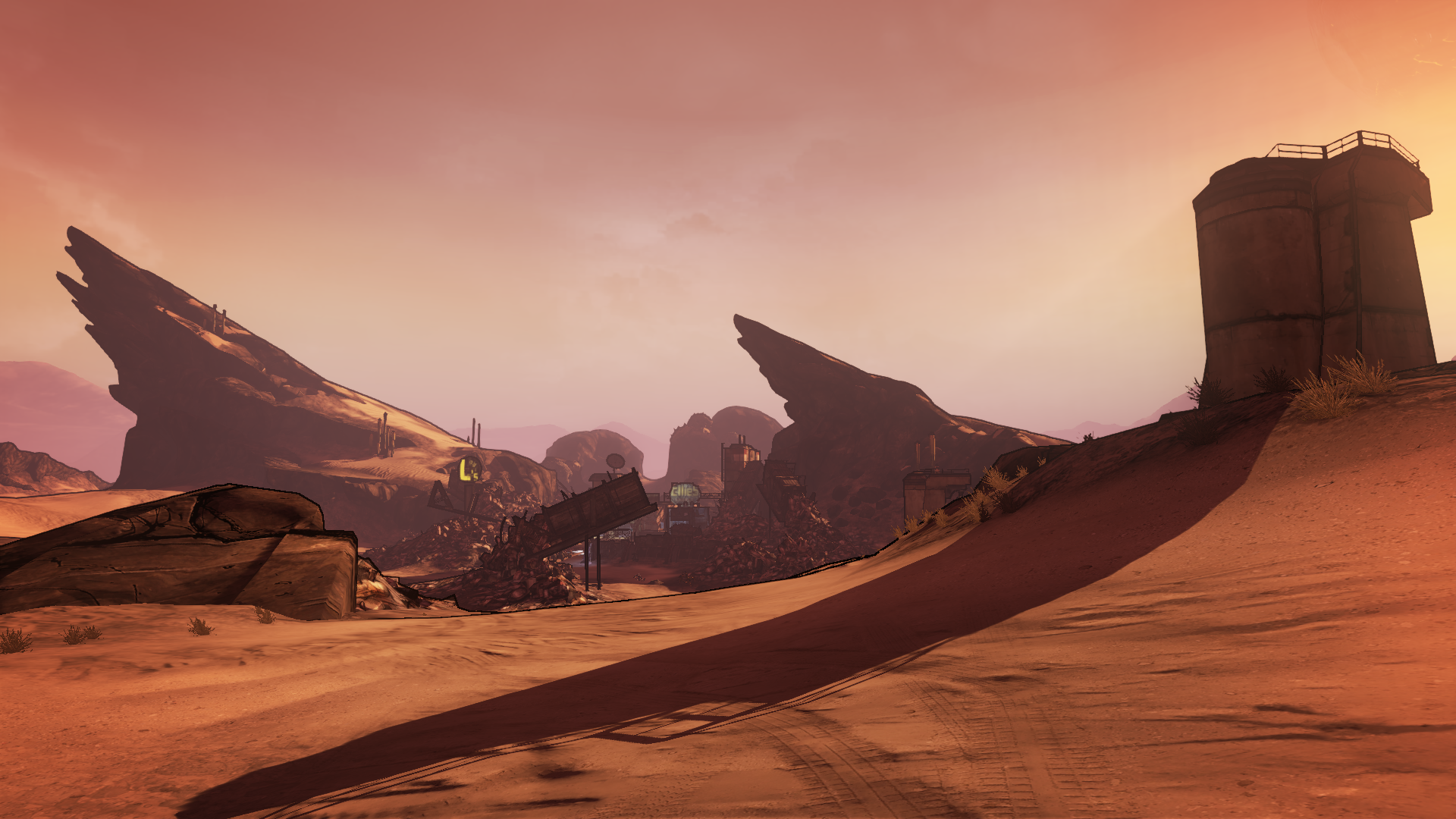

In the Borderlands, quality weapons are hard to come by. For every glimmering golden hand cannon prised from the maw of an elder god, there are thousands more waiting to be plucked from dirt piles and lifted from lockers. Before coming into possession of a 90-round spitfire that fires with the precision of a targeting laser, it’ll be rusted rifles with broken stocks and beaten iron pistols that you point at the inhabitants of Pandora. The road to the perfect set of gear is paved with common fodder.

It’s quantity before quality, but there’s a lot to be said for the generosity at the heart of Gearbox’s Borderlands series, where new armaments quickly pile at your feet, and cash becomes less valuable than the paper it’s printed on. Across Pandora and its lone moon, Elpis, colonists arm themselves so that they can stave off predators, bandits stockpile weapons in order to ward off outsiders, and arms corporations power production lines so that they can ensure their monopoly remains unchallenged. The galactic frontier holds many secrets—of forgotten treasures, alien relics and ancient technology. As the tribes of this isolated new world engage in a war without an end, the only assurance is that the cost of survival is paid in bullets.

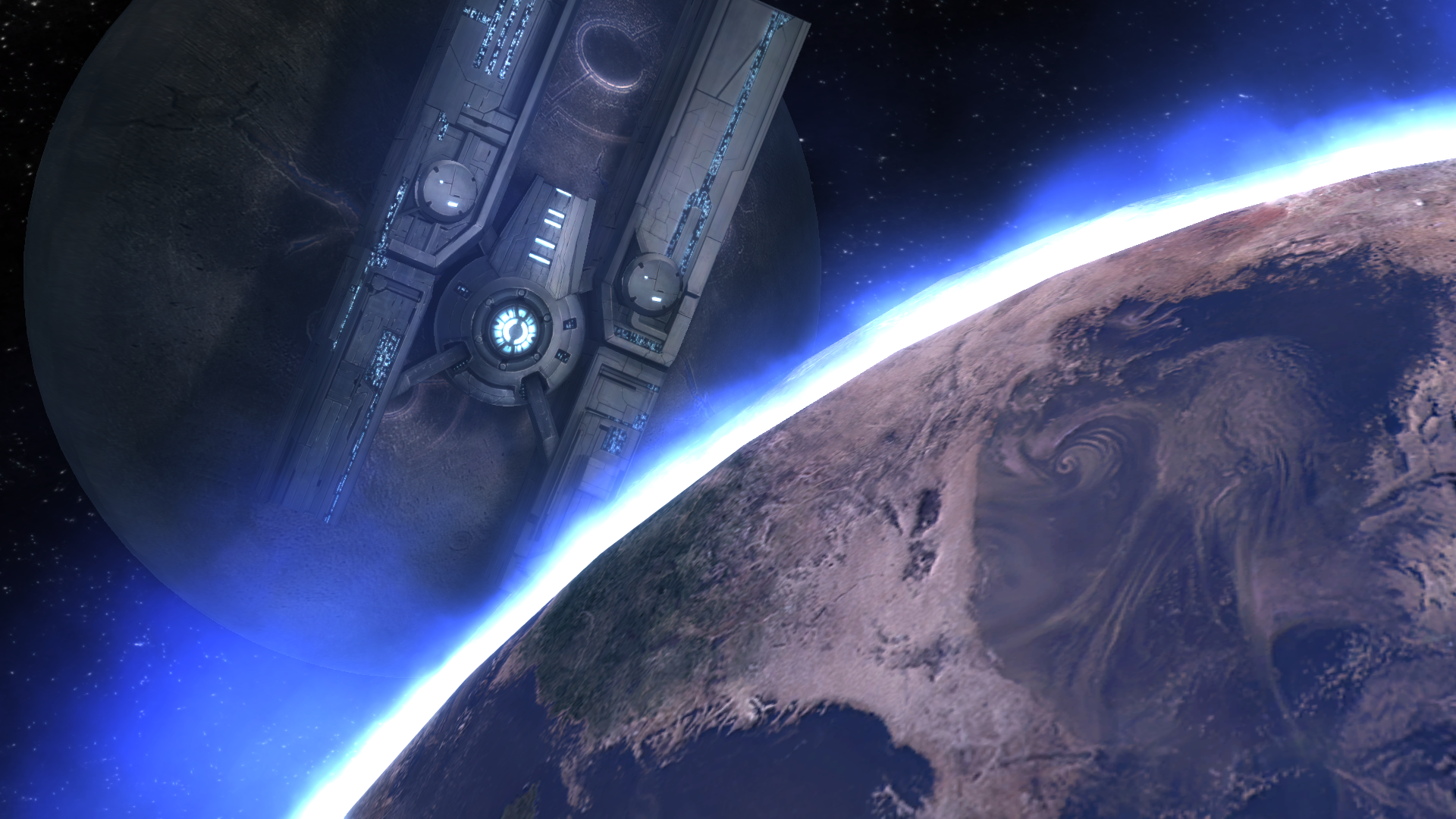

The first glimpse the world had of Borderlands 3 unsurprisingly played to the game’s strengths. The focus was on guns: guns billowing smoke from electric coils, guns with drum magazines the size of wheels, and guns that trundled across the battlefield on a set of self-deployed legs. Nestled in between this showcase of weaponry were glimpses of characters old and new, and of worlds beyond the trash-laden planes and violet skies of a now familiar Pandora. Where once the golden text emblazoned across the game’s cover had tantalised us with millions of possible weapon variations, now we were being promised bazillions. A lot of guns then, but a statement that was little more than a reiteration of the series’ prevailing sentiment. ‘Shoot and loot’ was how it had been since the original Borderlands had released back in 2009, its inspiration rooted in games such as Diablo and Ultima, with its influence still felt in the likes of Destiny and The Division over a decade later.

It’s a remarkably simple premise, and a large part of what made the first Borderlands so popular. Canonically, the result of a prisoner uprising against the arms manufacturers that used them as slave labour was a lot of unhinged psychopaths, and an abundance of weapons rife for the taking. Practically, Gearbox took the diluted sense of progression that accompanied the slow grind through typical RPG character levels, and injected it with a touch of adrenaline. Your rise from hapless mercenary to Vault Hunter extraordinaire wouldn’t be defined by the search for a single rarified weapon, but rather a perpetual pursuit of more. It began with white rarity weapons, which would quickly give way to green, then blue, purple, and eventually, orange. The strongest, most unique tools that the game had to offer were signified by their burnt gold moniker and a dash of crimson flavour text. But even they had a half-life when acquired prior to hitting the level cap. Only when you had wrung every last drop of experience from a campaign and several DLC expansions did the game’s inherent flux begin to subside. Only after felling every single beast, boss and bandit could you then stave off the treasure seeking and dumpster diving, muscle memory permitting.

* * *

The 2019 re-release of Borderlands came at just the right time. Off the back of the worldwide premiere of Borderlands 3, the urge to return to Pandora for one last pass gradually became stronger, and before long, a one-off trip to the planet’s eastern coast had turned into an all inclusive expedition, with room still for a detour to Elpis via the Pre-Sequel. It was through the Handsome Collection that I had first sampled what Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel had to offer, and not too long ago that PlayStation Plus had presented me with a chance to try the narratively driven Tales from the Borderlands for the very first time. More than anything, it was my first opportunity to play the series from beginning to end, and commencing that by first picking up a game that I hadn’t returned to in the last near-decade since its release. In that time, the Borderlands series had become Gearbox’s flagship, a diamond in the rough of games plagued by mismanagement and dogged by controversy. And even it wasn’t left unscathed either, with the team at 2K Australia disbanded shortly after the Pre-Sequel, with the original Borderlands too mired by a furore regarding its last minute pivot to an entirely shaded aesthetic.

From what little I remembered, it became clear rather early on that the biggest change had occurred not with Borderlands, but within myself. Where once I was content to amble from point to point, following the path set by the directional diamond without so much as a single deviation, now, I wanted to see it all and experience everything on offer. Though the wealth of content that I had remembered Borderlands for wasn’t so eager to present itself. Side-quests were generally inconsequential against the backdrop of the main narrative, and the game’s strange pathing an annoying hinderance to consistent progress. Back then, myself and a few friends spent hours upon hours of after-school sessions in the Borderlands, oblivious to the notion of timely completion or perfectionism. But now, it hadn’t taken us very long at all in order to blow past Sledge, Krom and Flynt, with the climactic final face-off against the Destroyer setting us back a little over a minute. This time, victory wasn’t snatched from the jaws of defeat, but rather nonchalantly pawed at with the least amount of effort possible. In our desire to take a final, lasting impression away from this precursor Pandora, every last drop of experience had been wrung from every possible source. The downside to this, of course, was that completion of every side-quest had seen us burn though enough levels to make every foe that stood in our way feel distinctly underwhelming. Even the game’s titular raid boss, Crawmerax the Invincible, hadn’t posed too much of a challenge by the time that his minions had been swatted aside. The game’s level scaling was just too rigid to keep up with our own inflexible box-checking, and in that, our virtual tourism a meander where once it had seemed a marathon.

Avoiding the remastered moniker, Gearbox instead christened this updated Borderlands as the ‘Game of the Year’ edition, bringing with it every piece of content the game had to offer, while also divulging a few select improvements to performance and visual fidelity. For the first time, the original Borderlands was playable at a smooth and consistent 60 frames-per-second, with updated high-definition textures brightening the game with one final earnest swab of polish. And what’s more, for console players, the addition of an FOV slider was a particularly welcoming sight, the pastel scape of Pandora’s destitute coastline looking sharper and more appetising than ever before. The prevalence of many of the game’s suspect design choices are what keep it rooted in the past however, with technical adjustments taking precedence over more practical ones. This is still the first Borderlands as it ever was, and that means poor level scaling, uninventive character archetypes, and oddly, a distinct lack of variety in loot. Pandora is still desolate and unerringly quiet, with the story that it tells and the lore it creates elevating the world around it much more than many of its forgettable boss encounters or irreverent side-quests. The Borderlands Game of the Year edition adds a welcome touch of colour to a world that I’ve already spent a lot of time in, while remaining stubbornly faithful to the game’s original form. And if anything, its truthful recreation certainly assisted in contextualising the mammoth improvements that would inspire its sequels. Though, I can’t help but wonder what it would be like to have an additional fast-travel point along the T-Bone Junction highway.

Borderlands 2 would release a few years down the line following on from the breakout success of the original, but chronologically, it was the story as told within the Pre-Sequel that would first expand on the series’ overarching narrative and growing lore. Wedged in between the two mainline games, the Pre-Sequel assumed the role of a deluxe expansion rather than the third instalment within a trilogy—its name even serving as a riff on its own awkward emplacement. And it would receive generally positive scores from critics too, but many of them would point to the lack of innovation that it offered as its biggest impediment. Even when marketed as something of a stop-gap for the series, the Pre-Sequel struggled to rid itself of the overwhelming expectation that came as byproduct of its predecessor’s success. For those who played the story once over from beginning to end, the game was an inoffensive, engaging experience that helped further characterise the evil intent of the series’ greatest antagonist. But after Borderlands 2 first outlined its commitment to repeated play-throughs, hitting the level cap and pursuing marginally greater stats, the notable reduction in scale of the Pre-Sequel’s endgame undoubtedly counted against it. Next to a shorter campaign, fewer side-quests, fewer raid bosses, a smaller pool of legendary weapons and only a single substantial DLC addition, it lacked the ability to motivate players in the same way that Borderlands 2 did. For all of its issues, it was the lessened emphasis on extensive post-game levelling and looting that certainly stood out the most.

* * *

It was a Borderlands-lite that arrived when fan demand rallied for something more substantial. The Pre-Sequel may have not fit the bill, but neither did something that was prised apart from the Borderlands series entirely. The ill-fated Battleborn was deliberately paralleled with Gearbox’s FPS flagship in its marketing, advertisements promising that this was the bigger, better experience that the Pre-Sequel had only ever hinted at. The result was something much less captivating, the game dying an agonising death in double-quick time and leaving behind many of the same cravings for a deep, rewarding looter-shooter that had first incited its conception. If anything, Battleborn’s sole success was in raising the stock of the Borderlands brand by failing to replicate its core strengths so spectacularly—a pitfall that the Pre-Sequel had avoided, despite fumbling in other areas. As Battleborn burned out leaving only a void in its wake, suddenly a return journey to Elpis didn’t seem like such a bad proposition.

Where the Pre-Sequel faltered when it came to building the player’s character, it excelled with its renewed depiction of Handsome Jack. Such was the popularity of the nefariously wretched leader of the Hyperion corporation, that the Pre-Sequel sought to elaborate on his character all the more, filling in many of the blanks that Borderlands 2 had only skimmed over. It didn’t matter that the game’s story recounted the devolution of an antagonist we had already killed and the backstories of Vault Hunters whose fates had already been written. Jack was such an alluring villain that any excuse to spend a little more time drawing his ire was indisputably worthwhile. As Jack’s tale first began, he was a fresh-faced puppet within a company that considered him entirely expendable, caught in the middle of a siege at the hands of rival arms manufacturer, Dahl. But, from the moment that Dahl’s ambitions had become his own, Jack’s morality began to waver, his naivety gradually washed away by a growing lust for magnanimity. Betrayed by those he confided in who feared what they began to see behind his eyes, Jack donned his mask and set to work unearthing Pandora’s secrets. No more dissent, no more rivals, and certainly no more Vault Hunters. A worthy tale of origin for someone we had all already revelled in killing over and over again.

Jack’s time atop the Pandoran heap wasn’t all just blood and bots, though. The Pre-Sequel introduced many mechanics that improved upon the series’ own loot and shoot cycle, many of which served as a solution to already existing issues. Oxygen kits made for a more enjoyable method of traversal, cryogenic damage was a much more sensible replacement for slag, and the introduction of the weapon grinder gave even the worst armaments a chance to become something greater. Meted in between evident problems were glimpses at what the next major Borderlands game could entail—one in which the steady flow of newly introduced features were condensed into something more palatable. Ideas that could help evolve the series for the better, otherwise left to waver without ever being fully realised.

As the expedition brought me back to the bus stop in Fyrestone once more, Saturn’s shadow looming large over the town where it had all began, Borderlands 2 had few secrets left to surprise me with. And that’s to be expected really, given the numerous play-throughs I had completed across all six characters, first on the Xbox 360 and now here, on the PlayStation 4. Buried deep in the recesses of my memory was every reference, joke, strand of dialogue and legendary affix. Clinging to my periphery, reflections of years spent gun running and bullet spitting from Sanctuary to Wurmwater, the Unassuming Docks to Opportunity. Borderlands 2 was the quintessential looter-shooter, the greatest realisation of the collect-utilise-discard cycle, and one of my most played games ever. And since its original release back in September 2012, its influence had extended to many of the other titles that sat alongside it in my library—the game’s legacy enduring as the term loot became synonymous with plentiful generosity, at least when it came to quantity.

* * *

The popularity of Borderlands 2 wasn’t solely due to the success of its gearing system, but was also earned through a renewed commitment to the game’s narrative and quickly expanding lore. Such a recurrent experience demanded a story as compelling as it was fulfilling, and in recounting the downfall of Handsome Jack alongside the rise of the Crimson Raiders, Borderlands 2 had taken to embracing the broader aspects of its whole experience. Running parallel to Jack’s quest of waking the Eridian Warrior was a story all your own—you were a second generation Vault Hunter whose predilection for scavenging riches just so happen to interfere with Jack’s desire to completely purge a whole planet. And in order to beat him back, you were going to need all the help that you could muster. The original four Vault Hunters you had first explored Pandora with were now the ones calling the shots, while a pre-existing ensemble of support characters would return to lend their aid too. Everyone in some way had been affected by the dastardly Hyperion corporation and its impervious reach. Everyone had a bone to pick with the man in the mask.

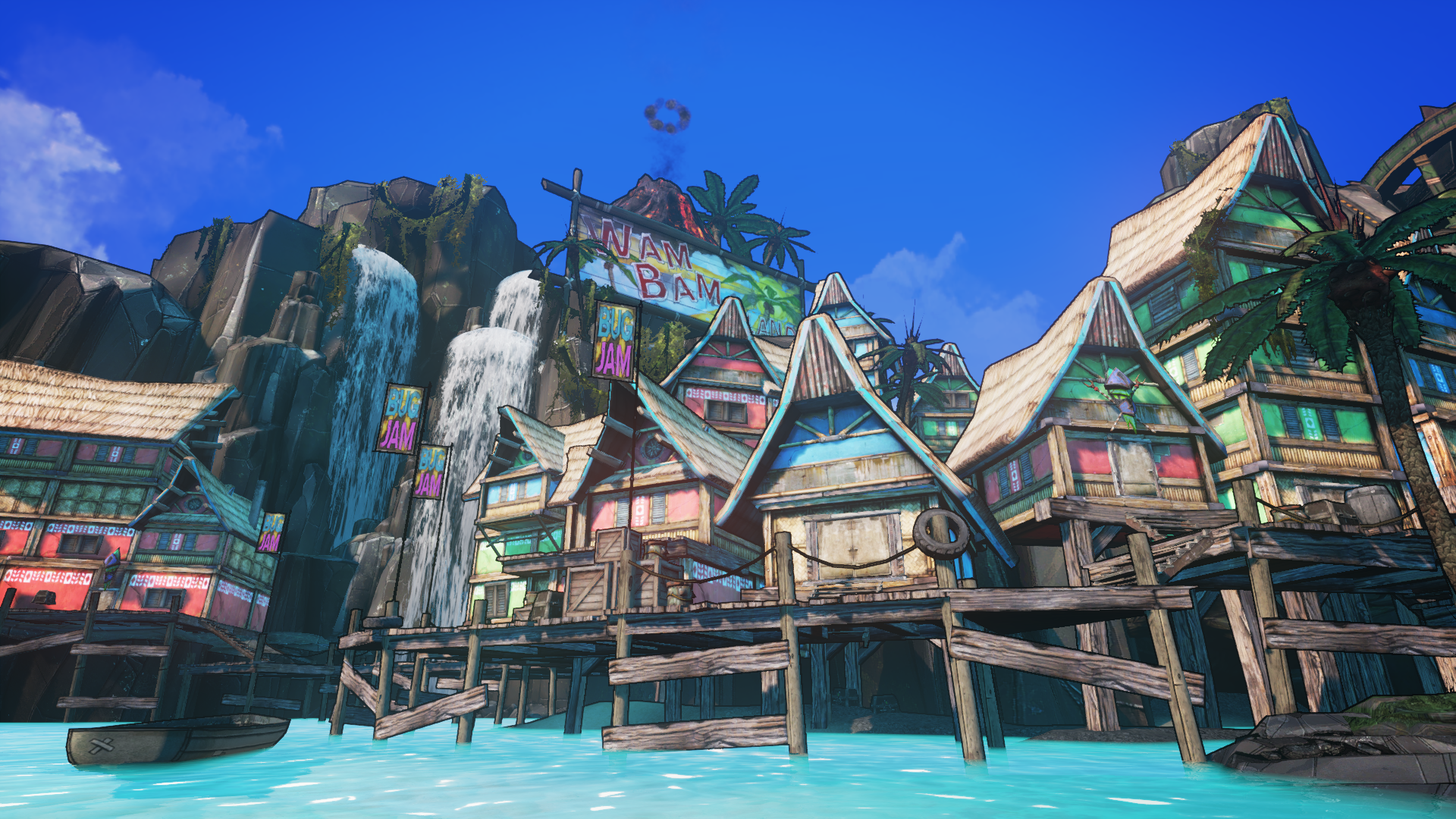

Returning players all had a history with the original four, and to see each of them make their reintroduction felt as though the series was steadily becoming something bigger. Not having their personalities confined entirely to ECHO recordings or mid-fight boasts, now our favourite characters were vocal, animated and a large part of what gave Borderlands 2 such a vibrant palate. And they all contributed to making Pandora seem much grander than ever before. As a hunter missing several of his limbs challenged you to pursue some of the dormant beasts lurking in Pandora’s furthest corners, and an eclectic CEO obsessed with explosives beckoned you to compete in his own tailored brand of death-matches, the Trash Coast seemed a long time forgotten. With every new quest offered up by Lilith, Roland, Brick and Mordecai, we were treated to a side of Pandora we had never seen. If it wasn’t the burning velvet skies of the Eridian Blight or the bubbling acid pits of the Caustic Caverns, then the game’s extensive DLC collection would take you everywhere from foggy swamp grottos to quaint Christmas villages. It was seemingly by sheer luck then, that my final voyage across Pandora would coincide with the game’s first major DLC release in years, with Sanctuary, the Crimson Raiders and the entire planet given a final, climactic sendoff.

It was almost as if everything that Borderlands had come to be known for up until now was boiled down into a single, succinct package. The Fight for Sanctuary, which posed as a bridge between Borderlands 2 and 3, brought back everything from raid bosses to character splash cards. Importantly, it also clarified its extended lore for those unfamiliar with Telltale’s contribution to the series, namely by integrating characters from the wildly successful Tales from the Borderlands into the main game alongside established favourites. The ensuing destruction of Sanctuary that finally concludes the story of Borderlands 2 was surprising, but it also indicated something of a fresh start. Borderlands 3 will represent the first mainline release for the series since 2014, and for those who have spent the years since then wracking up air miles between Pandora and Elpis, its release will come as a welcome relief. But it’s not just a change of scenery that’s sought after, rather the necessary adjustments to the game’s core that reshape it for the better. Scattered across all four games are a litany of encouraging ideas in need of refinement, while in its absence, several of the series’ many contemporaries have made improvements all their own. Borderlands no longer exists in a bubble, but that may not be a bad thing. Life after Jack was never going to be the same, anyway.