As soon as the rusted bolts on the iron door of Vault 111 were unclasped and the beams of light first penetrated its walls, so began the rapid moral devolution of my character. It’s just unavoidable. To exist in the new world is to breathe in the foul air left in the wake of the old one, and to be consumed beneath its impenetrable shroud. In the new Commonwealth, clearheadedness is a foreign concept. For permeating every inch of the scorched earth is a thick, dreadful smog that chokes and infects without prejudice or remorse. It sets darkened rings around the eyes and weighs heavy on the head. And it releases you from any semblance of purity that had been preserved by cryogenic slumber. For in the world beyond the bomb, only the impure exist, and only the impure fight the war of eternal survival.

Fallout 4 isn’t a game that burdens you with a human conscience. There’s no room for living justly in an unjust age. Upon stepping out from within the vault for the first time, it was under an hour before I had killed my first man. Under three before that kill count was in to double figures. Under four before I had extorted money from another. All mere distractions along the path to finding my son, all righteous acts as long as the other person deserved it. Every action only holds as much moral significance as you allow it to, however the cumulative weight of your every decision, like the air we breathe, hangs heavy regardless. To know that your decisions are inherently bad means naught when you and the people that you care about are in constant danger. Achieving tranquility in the wasteland is unfeasible so as long as survival remains paramount. And evidently, it’s the will to survive that drives the incessant hoarding of ammunition and the crafting of potent narcotics from surplus medication. Like many things in the warped world of Bethesda’s Fallout 4, even the moments of clarity are artificial.

The first time I inhaled a homemade batch of UltraJet, I was being pawed at by a grossly disfigured American black bear. But as the drug took hold of my system and I became enclosed within a bubble of tempered time, there was the clarity that had thus far eluded me. Things were quieter now, save for the bear and I, engaged in a duel far removed from the clutches of post-nuclear civilisation. He charged, I reloaded, and in a lucid haze of welcoming equanimity, I unleashed a torrent of red fire from my laser rifle, not stopping until the smoking cartridge had forcibly ejected itself from the stock. Every shot struck like a hammer on a nail, a clean burst of energy and sound that was gone as quickly as it had arrived. And as the bear sluggishly tumbled to the ground, with a rotten Commonwealth steadily easing its way back into my periphery, the hallucinogenic bout of ultra-violence had concluded, its victor a girl with a racing heart and gritted teeth. ‘UltraJet has worn off’ read the tooltip as the drug loosened its grip on my senses. A lukewarm, irradiated gulp of Nuka Cola Cherry would take the edge off for the rest of my journey across the eastern moors.

This is the cost of survival in the wasteland. Drugs, violence, compromising your ideals. And yet none of this comes without some sort of structure. In Fallout 4, society has accepted its fate and chosen to continue on in the wake of the apocalypse, and as such, there’s a strange air of normalcy to everything. Crafting medication, as well as some of the aforementioned enhancers, is just as accepted as it is expected. And honing your arms for the fight ahead is similarly ingrained into the gangs of bandits and mercenaries that await outside of Vault 111’s long-forgotten corridors.

COMPANIONS ARE EACH DERIVATIVES OF A MALIGNED SOCIETY

Weapon crafting in Fallout 4 gives you the chance to make something of worth from even the most dilapidated of armaments. Guns are in no short supply in the Commonwealth, with the most readily available being the homemade ‘Pipe’ variety that you’ll have likely plucked from the pockets of your defeated. These weapons are largely unrefined husks of wood and steel, but they do a decent job when it comes to offering personal protection against some of Boston’s less rugged foes. You can chop and change these at will using any weapon modification station, but putting your everlasting mark on something a little stronger undoubtedly brings another dimension to the concept of weapon ownership. In the wooded area behind the houses of Sanctuary Hills, I stumbled across a tattered hunting rifle propped up against a wooden stump. It was a throwaway find really, something to use until it was quickly superseded by a rifle of greater power, or something to sell to the nearest vendor for a quick buck. A lack of options at my present level afforded it the chance for some extended use, but it was Fallout’s implicit emphasis on making something out of nothing that demanded the rifle be given the opportunity to fulfill its potential.

The gleeful marksman in me settled on the moniker ‘Gratification’, and with each staggered upgrade over the course of my playtime, Gratification became something more. An extended magazine brought Gratification Mark II, a refined barrel Mark III and a better stock Mark IV. By the time that I had tailored the gun to my exact specifications, it was almost unrecognisable from the wasteland flotsam it once was, faultless in both presentation and application. It’s ‘Gratification Absolute’ now though, and almost in spite of the Commonwealth’s rusted cars and crumbling towers, there’s not a single blemish along its perfect frame, save for the occasional speckle of Super Mutant grey matter. And through a combination of a refined ‘VATS’ system and the games superbly polished shooting mechanic, every shot from its chamber feels clean, every killing blow sharp and satisfying. Weaponised combat in Fallout 4 is the most wonderfully responsive it has ever been, and it was through Gratification that the extent of the improvements to the games gunplay became truly apparent. Just as every kill you make in Fallout 4 is greeted with the decisive ring of an experience point gain, so is every felled opponent also met with a sense of wicked delight.

It wouldn’t have mattered if the tweaking of my rifle had not amounted to any sort of passive EXP gain, either. Weapon crafting in Fallout 4 isn’t particularly deep, but it is tremendously rewarding knowing that something crafted and created through your own workmanship is now culling bandits region-wide. And it’s this process of creating much from little that props up Fallout’s typical fare of questing and exploration, with the new settlement mechanic at the heart of it all.

From very early on in the game, you’re actively encouraged to build domiciles for the Commonwealth’s downtrodden, but more importantly, you’re being gradually shifted into a state of synchronicity with the games ‘use and reuse’ carousel. In Fallout 4, everything from the lead pipe to the crystal decanter has a purpose, with their usefulness being determined by the raw materials that they break down into. Constructing a survivor settlement that is as functional as it is eye-catching is going to take time, sure, but it’s also going to take a plethora of items that vary from the structurally essential to the almost forgetfully minute. In prior Fallout games, the invisible burlap sack draped across your shoulders would be reserved almost exclusively for weapons and rarified collectibles, but now, it’s packed to the brim with the trash from which you will create a paradise of wood planks and wrought steel. But settlements are for your benefit as much as they are the destitute of the land, and presiding over their populace as some sort of mayoral figurehead can be as frustrating as it is devilishly enjoyable.

When Sanctuary is your primary focus, the settlement system moves at a perfect pace. You’ll venture forth with a few locations to check off, and return home, pockets full of utensils just waiting to be reverse engineered into generators and jukeboxes alike. But there are some 30 or so unique settlements in Fallout 4 that will all eventually be vying for your attention, and maintaining each of them next to naturally progressing through several different plot-lines just isn’t possible. A few of the games repeating radiant quests will have you free potential new locations from the burden of their monstrous inhabitants, but unless you’re willing to pledge yourself to that location long-term, it’s new occupants will spend their days pacing in circles, drifting between the unattended vegetable patch and the vacant cooking stove. Anything less than your complete and utter servitude, and that settlement will never prosper. And as the problem becomes multiplied with the introduction of every new lifeless hovel, the settlement system becomes something of an exercise in spinning plates.

FALLOUT’S ULTRA-VIOLENCE IS STILL BRILLIANTLY OVERPLAYED

To call a place your own and dedicate your time to its restoration is still a worthwhile undertaking though, even if it means that you decide focus all of your efforts on a single place rather than diluting your resources across several. My incarnation of Sanctuary is home to a Power Armour compound, a small farm, a bar and a marketplace. It’s propelled by a wave of light and sound and is my chosen home post-apocalypse, just like it was in the centuries before the arrival of the nuclear fire. For my settlement to evolve into its present township state though, many battles still had to be fought along the way, but not necessarily against those looking to raze it to the ground. Erecting structures is never problematic so as long as you colour within the lines, but from the moment you begin a new project of adding a perimeter fence or a security checkpoint outside of the few designated plinths, building becomes far harder than it should be. No object clipping means many different pieces simply won’t coexist, and uneven turf leads to others floating a few feet from the floor. And just as inherent to settlement building is the disappointing notion of having to alter your plans when a wooden wall just won’t fit where you’d like it to, or when decorative items won’t cease falling through the floor. Pulling a vibrant homestead from the ashes of a vitrified earth is immensely gratifying, but it comes with an impassable caveat – the bigger your ideas, the more ways there are for the game engine to constantly hinder your progress.

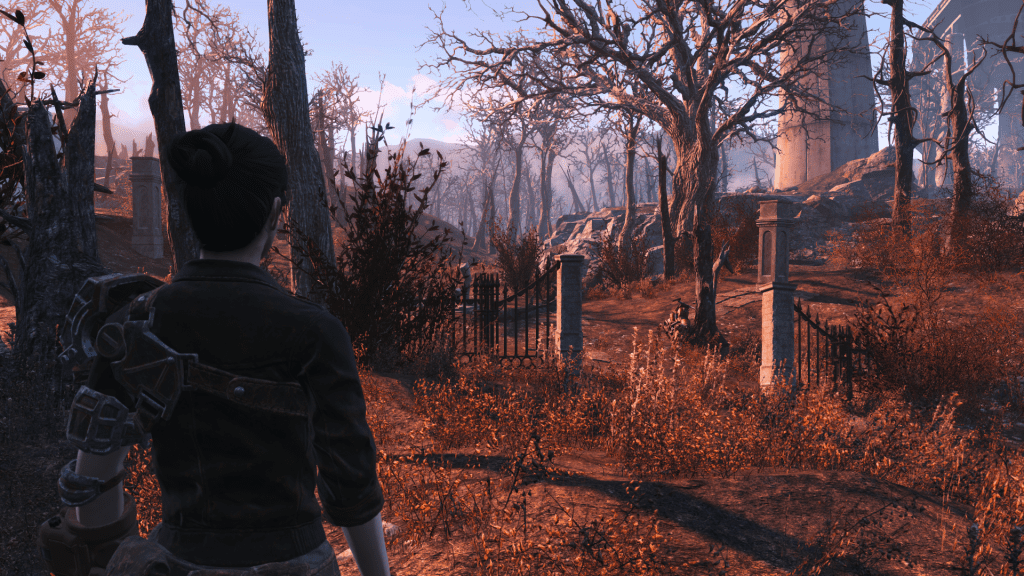

Despite the sparkling allure of Diamond City, Sanctuary Hills remains my haven of choice. And yet the Commonwealth in Bethesda’s Fallout 4 is home to many landmarks far out of reach of Sanctuary’s welcoming hearth. Much of Fallout 3’s naturally horrific ambience came from its colour palette, which favoured a darkened morbid reality over that of a more vidid post-apocalypse. The greens and greys of its fractured lands made everything overplayed on top of it feel that much more terrifying, and while Fallout 4 can’t lean on the same crutches, it does make the most of its evidently more inviting landscape.

Rather than emphasising the impact made by every ember that singed the earth on that fateful day back in 2077, Fallout 4 instead attempts to recall the world that existed prior, harkening back to its frighteningly twisted American Dream mystique and the wonderful irony of its atomic worship. In the few moments that you exist before America’s opulence becomes reduced to ashes, the rampancy of the country’s materialism is proudly paraded. Rows of freshly-coated picket fences are interrupted only by cheaply made sedans, while at the end of every road sits the fire-red fridges that house the addictive elixirs of the Nuka Cola company. Heavy-set televisions beam into every living room and personal robotic assistants glide between the kitchen and the laundry hamper. This visual realisation of an unblemished America may have been as subtle as a Deathclaw swipe across the jaw, but the true success in Fallout 4 lies not in the recreation of the past, but in the resurrection of its sickeningly manufactured culture over two centuries later.

Knowledge of the foreign Commonwealth is pieced together through a combination of plot revelations, computer terminals and holotape recordings, but most enlightening is natural discovery through aimless exploration. Like many Bethesda RPG’s before it, Fallout 4 is still a game that encourages you to get lost when roaming, burying you beneath a wave side-quests and random encounters. And the thrill of exploring the unexplored hasn’t faltered, particularly when your character approaches everything with a similar level of unknowing. The further you dig though, the closer you’ll likely find yourself to the dark heart of pre-apocalypse civilisation. In Fallout 4’s incarnation of Boston, the vehicle production plant and food packing facility were just as susceptible to the stranglehold of corruption as the government office or the military garrison. And it’s why every surviving poster for Sugar Bombs cereal and every untainted Nuka Cola fridge exist with a somewhat haunting presence. It’s only through charting the whole region that you will uncover the extent of the old world’s ills, and only then that you may even come to appreciate the impact of its subsequent nuclear annihilation.

But the mistakes made by humanity are cyclical, and so the threat of further destruction lingers even after the bombs have fallen. In DC, it was a lack of clean water killing off wasteland inhabitants, but in Boston, it’s synthetic humanoids. Almost everyone that you will meet on your travels has an opinion about ‘synths’, such is their role in being the regions greatest instigators of fear. Murders, abductions, societal manipulations – it all leads back to synths, and by association, the menacing Institute from which they arose.

The games crux is in dealing with this synth epidemic, and in allying with a single one of four divisive factions so that they may help you put an end to this perpetual strife. A structured storyline ties everything together well, and while it actively encourages you to debate the very definition of humanity, it is plainly lacking in many humanistic qualities itself. Choice in Fallout 4 is present only to benefit the furthering of the plot and not the development of your character. To view yourself as a stoic, emotionless figure is to be only allowed to respond to dialogue through gushing outpourings of grief. And to approach a quest with a specific line of thought is to see it boil down into two very obvious paths. Quests in Fallout 4 are expectedly enjoyable, particularly since they introduce you to so many of the warped and weird that inhabit greater Boston, but the limiting freedom of your involvement in their outcome is a blight an otherwise open-ended experience. A typical interaction in Fallout 4 offers the right answer, two wrong answers and a sarcastic retort. And despite your evident emotional anguish, you’ll have the chance to fire off these redundant sarcastic jibes at will from the moment you first reconnect with your fellow man. You were a wasteland wanderer by definition from the very moment that you exited the vault, yet at few points during Fallout’s heft do you ever feel truly in control of your own direction. It’s with a touch of bitter irony then that in a game about the shared existence of those mortal and those manufactured, you’re deprived of a such a defining human quality.

BOSTON ISN’T DEAD YET – WARRING TRIBES VYE FOR LAND, FOOD

That Fallout 4 still occupies my thoughts even after I’ve parted from its company is a testament to the consistency of the developers at the helm. The world that Bethesda has built, its layers upon layers of unending details, its sickeningly vivid portrayal of nuclear psychosis, is so perfect in its realisation that at times it even comes across as unsettlingly normal. I’ve been here before, though. I still remember losing hours of my life to SKYRIM, braving its icy tundra in the hope of having the land relinquish its every secret. I built houses, vanquished ancient terrors, ripped the very souls from dragons. SKYRIM, just like Fallout 4, exuded a believability in itself that emboldened my every moment spent with it. And beyond the richness of its world was a spectacular level of substance that existed in parallel with such a fine level of craftsmanship.

But as Bethesda’s Fallout 4 has evolved in many ways from that of its numerical predecessor, its archaisms have become a little more pronounced. The aforementioned smokescreen that surrounds the games freedom of choice is undoubtedly Fallout’s greatest flaw, however it’s the graphical issues that are perhaps the most immediately noticeable. Certain larger structures pop into view abruptly, others seem comprised of hastily drawn lines upon second glance. Fallout 4 is no triumph in aesthetics, but then it never really needs to be. Fallout 4 is just so effortlessly immersive that you can almost forgive its shortcomings if only to spend more time beneath its irradiated skies. There’s no shortage of undertakings to devote your time to, nor different perspectives from which to view the world. Your adventures constantly shape you, and your every encounter goes a little way to outlining your prejudices. If the synthetic are to be eradicated without contrition or delivered from subjugation, then it’s by your will that it will happen. And though it may also be through your intervention that Boston ultimately prospers or perishes, there will always be enough time for you to partake in the little things.

It only took a few moments for the Third World War to resolve. As soon as every major country expended their nuclear arsenal, retribution turned to retaliation, which turned to regret. Upon leaving Vault 111 for the first time, I instinctively made for Sanctuary Hills and quickly set to laying down the foundations for its rebirth as a safe haven. In the hundreds of hours that I’ve played Fallout 4 since then, I’ve charted the Commonwealth several times over, toppling despots and eradicating remnants of the old world. But I always come back to Sanctuary. It was home then, it’s home now, and it’s something that I will gladly fight to preserve. In Fallout 4, to survive the apocalypse is to become an unwilling product of the wasteland. You can’t change that. But just how much you let the wasteland in is completely up to you. You were the person that you needed to be long before you ever slipped into that blue and gold jumpsuit.