“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness” reads the epitaph to Arthur Morgan, a final, fleeting memory of the embattled outlaw at the heart of Rockstar Game’s Red Dead Redemption 2. It would have been a fitting end to die in a crossfire, consumed by a hail of bullets cast from the barrels of a dozen revolvers. But Arthur’s final moments were a far cry from those of John Marston, a man whose pre-written history had not yet played out within the Redemption chronology. John’s demise was tinged with revenge; of the law who sought to punish him for his past transgressions, and of his own desire to see his former allies pay for their betrayal. But for Arthur, things were decidedly different.

The Redemption saga is Rockstar’s answer to a problem of their own creation, one in which its series’ protagonists are held responsible for their actions, this time shed of the immortality usually found in their modern world counterparts. For Arthur Morgan and John Marston, there was no endless summer awaiting their passage through the storm, no contentment to absolve their conscience. By the time that John had finally dealt with Dutch Van der Linde, his fate had already been sealed, for there remained no place in the new world for relics of an age defined by injustice and infamy. Spending his latter years suppressing the violent tendencies and wild blood of his youth, John was at least afforded the chance to bow with one final burst of fire and fury. Before a gauntlet of lawmen and marshals gathered at the gates of his secluded retreat, the last surviving member of the Van der Linde gang is granted the unspoken wish of a fitting end. A far cry from that of Arthur Morgan, who rather than rebelling against his death knell, instead met it with a begrudging acceptance.

In Red Dead Redemption 2, the morality of your decisions is depicted by the ‘Honor Meter’, a linear gauge that gradually fluctuates between its two polar extremes depending on your actions. Reining in the temptation to slaughter the populace of every town you visit, and, generally, your righteous level of restraint will be positively reflected. Though, should you move from state to state leaving only blood and broken bones in your wake, then the gauge will aptly tinge with a deep crimson red. The typical Rockstar protagonist is one who resides in the middle of these two extremes, a grey, unpredictable agent of chaos upon which players may project their destructive fantasies free of any tangible consequence. Aside from a few specific examples later on in the story, the Honor system never becomes anything more than a way to passively interpret just how much excessive killing you’ve done outside the bounds of the narrative. Murdering police officers and marshals, for example, is never met with repercussions so as long as it’s done at the behest of Dutch. It’s only when you preempt a shootout with an optional mugging that points for your apparent dishonour are doled out instead.

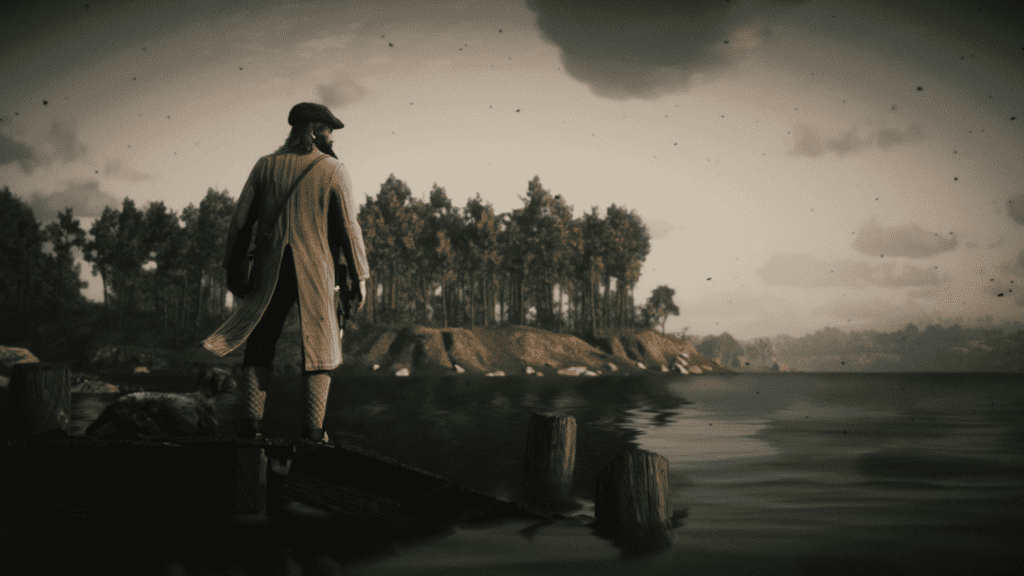

Yet even with the Honor system in place, indiscriminate killing and subsequent battles with the law are hard to avoid, especially when engaging in the world outside of the story regularly incurs the wrath of the law. The distinction between good and bad sits uneasily when dictated by a morality gauge, anyway. As the narrative of Red Dead Redemption 2 unfolds, Arthur Morgan is characterised with equal parts regret and naivety, rage and compassion. By his own admission, he isn’t interested in making amends out of some misplaced understanding of self. And he certainly doesn’t seek redemption. Where John Marston escapes to live for a time in exile, free of the mistakes of his past, Arthur is instead given little time to ponder the intricacies of his choices, even before he realises that the illness that has blighted him will soon consume him entirely. Arthur’s goal, his only goal, is to use as much time as he has left to help those that saw good in him, and those that expected better. Unlike many of the modern Grand Theft Auto titles, our character isn’t absolved by culling an antagonist—Micah Bell will always outlive Arthur, after all. By the time that the narrative reaches its last act, Arthur’s final flourish is one that seeks to validate our own personal perception of him. Either the favourite son of the Van der Linde gang was an irredeemable force of turmoil, or his poor choices were not damningly indicative of the man he truly was.

We’re given glimpses of the man that Arthur could become along the way, of past relationships that have faded from view and of confrontations best handled in a different manner. But even as Red Dead Redemption 2 draws so much attention to the dissonance at its heart, where the actions of our character aren’t an accurate portrayal of our own individual interpretations, there’s still enough room for Arthur Morgan to fit your intended image. And given the fluctuating polarity of his actions, self-loathing regularly met with wanton killing, it’s no wonder why the Honor gauge is such a prevalent fixture. I spent much of my time in Arthur’s shoes trying to be good. I greeted everyone I saw in town, even pivoting back in their direction to follow their response with a comment on the weather or the kindness of the locals. I hitched my horse rather than leaving it in the middle of the road, I threw fish I’d hooked back into lakes, and I spent time lending an ear to the whims and wishes of my similarly disaffected campmates. And all of this came naturally, except when accidentally colliding with a wandering traveller on horseback set me back in my attempts to keep the gauge rooted in its reflective state of absolute selflessness. For it was only ever by accident that the meter would plummet to the depths of depravity, hours of careful management undone by a moment of recklessness. Kindness, forever tinged by a muddied shade of grey.

Whether or not Arthur Morgan is ever redeemable remains subjective, but the inclusion of his decisions as a visible, calculable entity is not without its purpose. After abandoning the idea of throwing fish after hooked fish back into the river, my Arthur settled into his neutrality with great comfort, erring on the side of good without ever doing enough to fully succumb to the creeping chaos of the changing West. If Arthur, like the majority of the Van der Linde gang, was predisposed to be consumed by his way of life, then it was only in maturity that he came to understand the faults and mistakes of his youth. By boiling down the intricacies of his actions into points upon a gauge, we’re subjected to the same unwinnable moral quandary, with Arthur’s swansong a reiteration of the game’s lamentation upon the mortality of its protagonists. No matter the attempts to rectify their own ill will, morally unjustifiable actions bring with them fitting consequences. Though empathy isn’t something exclusively reserved for the righteous. As Arthur Morgan fights battle after losing battle, against his self, against his place in time, only the grey will remain as the rest of him fades away.