A feverish pace and insatiable consumption of every quest and compass point perhaps best outlined my initial journey amidst the white-capped peaks of Tamriel’s frozen north. The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim was my first exposure to a game of such size and detail – a near boundless RPG that had managed to hold my attention long after the conclusion of the prologue.

It arrived at the perfect time, as any hesitance in tackling a game of its breadth was slowly being eked away by the curiosity of finding out for myself exactly what resided in the deep water. At the time of originally playing it, Skyrim’s surface-level wonderment effortlessly outweighed the frailties visible at a more extended glance. And my return to the game via the Special Edition some five years later sought to recapture that initial astonishment, allowing the snow-covered scape to gently unfurl before me all over again. Yet it was a conscious understanding of Skyrim’s matter that would characterise my final ambling through its winding woodland pathways and rocky passages far more than a longing for renewal. A journey of recollection foremost that brought with it an unassuming intent for overwriting the already written.

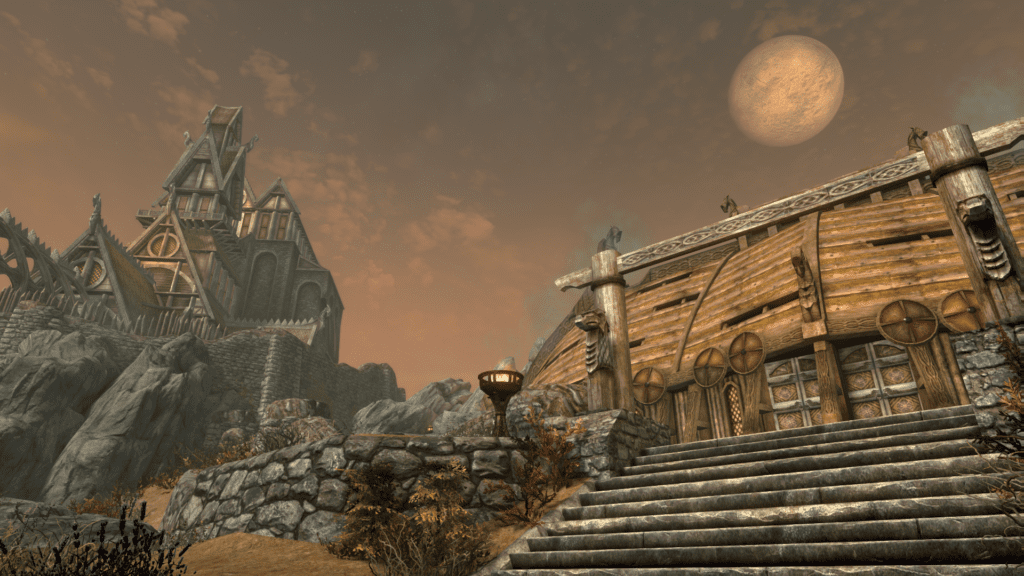

Before the dulling of Skyrim’s colours, the sight and sound of Alduin’s breath helped usher in that same bewitchment that accompanies the start of any journey seeking to pry away hours in their collective hundreds. I quickly outlined a path – Whiterun, Riften, Winterhold, Markarth. I wasn’t treading the same footsteps so as much as I was righting the wrongs of the piecemeal play-through that came before it. It’s difficult to account for so many loose ends when you’re left tumbling amidst the gales of quest completion and story progression. This time would be different. This time, it’d be a steadier course and fairer winds that carried me across the land.

And for a while, the difference of choices, of method and of direction afforded me the sense of rediscovery for which I had pined. I knew of the stories of Skyrim and their ends, but that wasn’t enough to hamper the paths that I took to reach them. And I knew the faces, many of which were freshly remoulded against the disposition of a far less compassionate Dragonborn. It wasn’t a canonical understanding that dispelled the stupor though. Instead, it was everything that had arrived in Skyrim’s wake following its original release. Skyrim was a marker point – a title from which blossomed a desire to branch out and seek its contemporaries for want of similarly-structured grand adventures. Its reach led me to devilish fantasy of Dragon Age: Inquisition, to the harrowing West of Red Dead Redemption, the grand space-scape of the Mass Effect trilogy, and even to Bethesda’s own charred atomic rises in Fallout 4. All distinctly role-playing games, all experiences which can be traced back to a precursor doused in delicate snowfall.

The death knell then was sent long before my Stormcloak sword-maiden ever reached the Throat of the World, ever slew Miraak upon the summit of Apocrypha. More so than any other, the corruptor extraordinaire was the finest game of its type that I had ever played – The Witcher III: Wild Hunt. The biggest success of the Witcher III was its magnificent weaving of a beautiful story, one that was espoused perfectly by characters as damnable as they were delightful, and one that tied the heart in knots with its elegance of delivery. The smaller successes were those that left a telling impression outside of the narrative – the times spent standing alone in the creaking forest, sun burning your back as distant brambles crack beneath the hooves of skulking beasts. There was no reprise for Skyrim once Solitude had become Novigrad, and Solstheim become Skellige. They were games of different times, but also games of far different reverence.

And so it was that the excitement of shrouding myself in snow once more did regress far too quickly. The pursuit of Mercer Frey; unintelligible. The battle against Alduin; unsatisfying. The world without the author; vacant and repetitive. Many marquee moments alleviated the fog somewhat – Miraak, Harkon, the defeat of every dragon priest. Many others only added to it. The end of Skyrim’s Civil War was the conclusion to my adventure, and though I had successfully completed every self-imposed objective I had set myself, it was an end that offered none of the conclusive satisfaction I had hoped would accompany my final moments beneath the shade of the hundred white peaks. I’d never see Skyrim like I did for the first time, and now that was all too clear.

Fallout 4 didn’t deviate too much from the template either. You could erect whole homesteads from the ashes now, yet there was no vigour propelling the story’s most lasting moments. It was switch-flipping, thin dialogue and a lack of conclusiveness. The General of the Minutemen was still a mule for culling ghouls and collecting crops. The saviour of the Commonwealth still a person to sneer at out of suspicion for being a synth. The modern Bethesda RPG, a culprit, and an otherwise antiquated taste.

At its best, Skyrim burnt bright and fast for a very short while. Slaying a dragon in a cinematically-driven cutscene outside of my homestead felt exactly as empowering as it should have. Delving into an occupied fortress and having my companion lose their life to a siege of Thalmor soldiers evoked the right tinge of anger. And shouting a Storm Call to the heavens whilst fighting amidst its hail plucked upon the perfect strings of valiance befitting of the Dragonborn. Reevaluating Skyrim became an exercise of extraction – salvaging the gems from the blunt ore in an effort to remember why it had resonated with me so much all those years ago. But really, my answer lied in the first few moments outside of Helgen, as a climatic battle chorus gave way to more sympathetic strings. You’re at a fork in the road – either you head to Riverwood, or you don’t. And I think that’s the aspect of Skyrim that endures in spite of the remaster. That’s what I’ll recall most fondly when I dwell on the swords and snowfall of Skyrim.